Saat Barbar Menggenggam Kejayaan Betbarian Bounty membawa pemain ke dunia fantasi epik, di mana para barbar bertarung untuk mendapatkan harta

Continue reading

Masuki Dunia Eksklusif Slot Premium | Di Sini, Setiap Spin Bernilai Nyata

Saat Barbar Menggenggam Kejayaan Betbarian Bounty membawa pemain ke dunia fantasi epik, di mana para barbar bertarung untuk mendapatkan harta

Continue reading

Knockout Football Slot: Saat Reel Berubah Jadi Lapangan Hijau Siapa bilang main slot gak bisa sambil ngerasain atmosfer stadion? Knockout

Continue reading

Dalam dunia permainan angka, memiliki pemahaman yang mendalam mengenai data keluaran adalah kunci untuk mengembangkan strategi yang efektif. Data keluaran

Continue reading

Castle of Fire menghadirkan pengalaman slot online bertema kerajaan api dengan mekanik expanding symbols yang agresif dan fitur free spins

Continue reading

Kekuatan Naga Bonsai dalam Blitz Penuh Kejutan Bonsai Dragon Blitz adalah permainan slot bertema naga oriental yang unik, memadukan filosofi

Continue reading

Menjelajahi Kastil Angker Demi Hadiah Misterius Horror Castle adalah permainan slot bertema horor klasik Eropa yang membawa pemain memasuki kastil

Continue reading

Industri judi online terus menghadirkan inovasi dalam dunia slot, dan salah satu permainan yang berhasil menarik perhatian pemain adalah Benji

Continue reading

Menyambut Keberuntungan dengan Bayi Lucu Fa Fa Babies adalah permainan slot bertema Asia yang menghadirkan bayi-bayi lucu sebagai simbol keberuntungan.

Continue reading

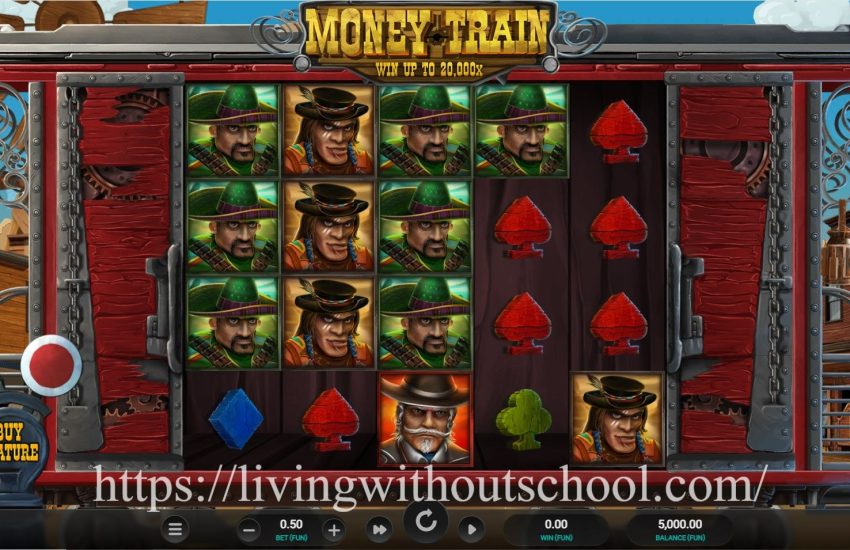

Aksi Perampokan Kereta dengan Hadiah Menggila Money Train adalah slot video ikonik dari Relax Gaming yang mengusung tema perampokan kereta

Continue reading

Dalam dunia judi online, game slot terus berkembang dengan menghadirkan tema yang menarik dan grafis memukau. Salah satu game yang

Continue reading